Tony Hornsby

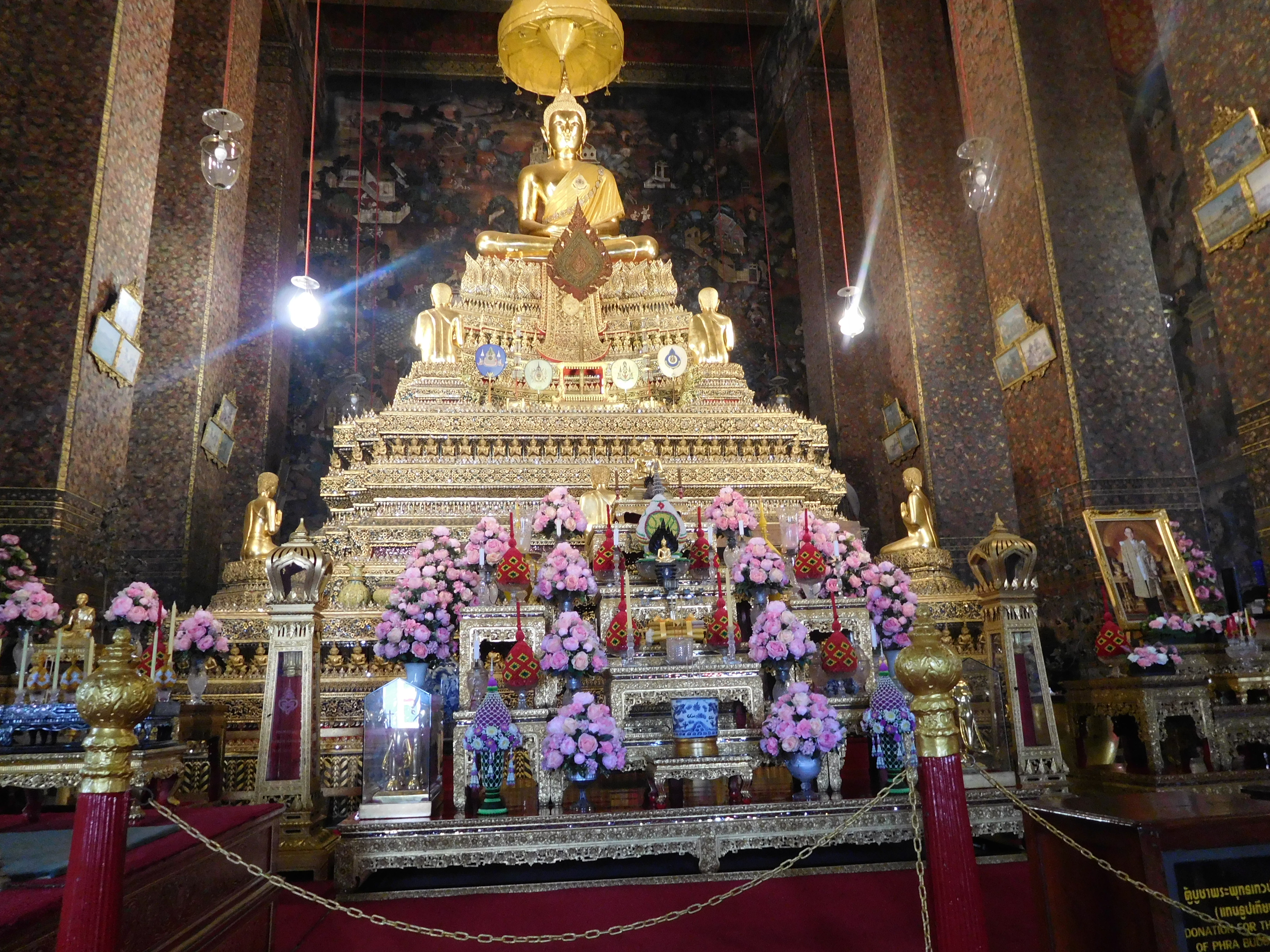

I walked silently through the Wat Pho Temple complex in Bangkok. A good portion of the temple complex is outdoors. All around me were people, mostly tourists like myself. Yet despite the people, the place was quiet somehow. Voices did not carry and the visitors instinctively kept their voices low, creating a silence that was as heavy as the heat of the day.

All around is an ancient feeling. The temple itself is not that old, having been renovated in the 1800’s, but much of its ornamentation is hundreds of years older, brought from other parts of Thailand to create this one sacred space. If you quiet your mind, you can feel the resonance of the monks that live here; who pray and meditate daily in this temple.

The most impressive portion of Wat Pho, however, is not the Temple itself, but a series of 4 walls facing inward to a courtyard. Standing sentinel along the perimeter of the walls are golden and black Buddha’s, slightly larger than life-sized, all standing facing the inward toward the center of the courtyard. Each Buddha has either one or both of its hands outstretched, palms up forming a square between the hand and the forearm.

The gesture seemed to be both one of benediction and of warding. Those who designed the temple complex were not ignorant of spiritual energy and how it flows, and walking through the courtyard you can feel the intent of the place. The Buddha’s gesture seems to say two things:

The first thing is: “This is a sacred space. The profane are not welcome here. All those with ill intent are not welcome.”

If you took a moment to look, you could see the effect of this. Some stayed and took pictures, awed by the area. Others moved past the courtyard quickly, to get to other parts of the Temple Complex or to visit the gift shop.

The second thing is: “This is a refuge for those who seek liberation from Dukkha. You are not alone. Many of us have tread this path before you, and we offer you our support, our wisdom and our benediction.”

The energetic weight of the place was almost overwhelming to anyone open to such things. Someone there told me that the Buddhas posted sentinel there were taken from Temples all over Thailand and other places in Southeast Asia. In many ways, these Buddhas, coming from all over, represented the entire spirit and wisdom of the Theravada Buddhism that dominates that part of the world. It made the place feel holy, larger, and older than it really was.

Walking through, you could sense the history that had been witnessed by these statuary sentinels. Originally posted all around Southeast Asia, they had been witness to generations of monks and laypersons who followed the teachings of the Buddha. They had stood guard before hundreds and, in some cases, over a thousand years’ worth of history. Then, eventually they found their way here; representatives of an ancient and still thriving Tradition.

The Buddhist Tradition thrives because it is eminently practical. If these Buddhist sentinels could tell us what they have witnessed of history, perhaps they would tell us about how little has changed. We, who gaze upon them today, likely came to be at the temple after driving a car, or taking a cab – modes of transportation that allow us to travel to distant places much quicker than human beings were able to travel when these Buddhas were created. We have smartphones in our pockets that allow us to record images of these ancient statues while at the same time give us almost instant access to an unlimited amount of information. Around the temple complex in which they reside, these Buddhas have witnessed the construction of a giant city. Bangkok sprouts up around them, an eccentric combination of modern skyscrapers and older, more traditional structures. Large shopping malls combine with local street markets to create an atmosphere that artfully combines modernity and ancient tradition. Planes fly overhead, carrying passengers from around the world to Thailand – covering distances in hours that would previously have taken months or years.

If these statues, these guardians of Tradition, could speak (and perhaps they can and do!) they may very well tell us that these technological advancements mean next to nothing. They might tell us that these things are tools, and that we’ve always had tools. After all, they could not be here, all in a row, observing the courtyard with their serene gaze, were it not for tools.

Their erect posture, their arrangement along the outside of the courtyard, and the precise placement of their hands remind us of intention. Whether it is a simple stone tool or a supercomputer, it is consciousness that directs intention; that determines the manner in which the tool will be used. Such tools can be used to create or destroy, to satisfy the appetites or to feed the poor. Is the wielder of the tool focused on selfish goals or compassionate ones? Is the operator of the technology fearful or filled with loving-kindness?

As I walked among the statues and contemplated, I began to see that I too, was an image of the Buddha just like the statues were. I had the same choices that Siddhartha had millennia ago. Three choices. After all this time, and all of the advancements of modern civilization, there are still really only three choices, and these choices have not changed since the time of the Buddha. Each of us have chosen each of the three choices thousands of times in our lives. These choices, made over and over again form habits. These habits inform the direction of our lives. So, what are these three choices?

Before we delve into choices, we must briefly examine the specific quality of nature that presents itself to us and prompts us to decide how we will act. This quality of nature is impermanence. It is a fundamental universal law that all things are constantly changing. There is a cycle to nature that cannot be avoided. If we are born into this world, then we will inevitably die. In the cycle of birth and death we encounter many other situations, such as childhood, adulthood, and old age. We develop relationships which change over time. We watch those we know and love pass away from us as mortality claims them. We experience happiness and we experience sorrow and pain. Even if we are healthy, we will all experience sickness at some point in our lives, and we will all eventually die.

Our minds do not like this impermanence. They just don’t function that way. Our minds like patterns. We come to expect to wake to see the sun rise each day. When we experience health and vigor, we become accustomed to it and our minds identify with it. We feel that it is a pattern that should be repeated. We seek to somehow prolong pleasurable experiences indefinitely and prevent painful ones from occuring. Even though we know that we will go through painful periods in our lives, and that we will eventually die, our minds tend to avoid this knowledge. Buddhism teaches that there are 2 methods that our minds use to help us avoid contemplating the reality of impermanence. These two methods are called “grasping” and “aversion.”

Grasping is that part of our nature that wants to hold on to something. Deep down we know that all things will eventually change into something else. That is great consolation when one has stubbed their toe on the coffee table late at night – the pain felt in that instance will eventually ease and go away. It’s not a happy thought when we are experiencing a pleasant situation or contemplating a happy relationship. Eventually the situation changes. The relationship changes. The pleasant situation becomes unpleasant. We are not good at accepting this fact, and what we do instead is try to hold onto the situation. This “holding on” creates a kind of negative feedback loop. The more we grasp at things, the more we identify ourselves with them. As we identify ourselves with a thing, situation, or relationship, we become fearful of losing that thing, situation, or relationship. The more fearful we become, the harder we grasp. This is called “attachment.”

Aversion is the other part of our nature. While part of us is grasping at the things we wish to hold onto, the other part of us is busy trying to avoid or ignore those things we don’t like. We avoid things that bring us pain and sorrow or cause us to become uncomfortable. The biggest source of aversion is the fear of death. Even though we all know that it is an eventuality for each person on the planet, many of us pretend that death does not exist. When hints of the inevitability of death creep into our world, we attempt to stamp it out. Many avoid and fear people who are dying. When the first gray hair appears on our heads, or the first wrinkle around our eyes, many of us reach for cosmetics of some sort to hide that reminder of our mortality. Certainly, some of this is vanity, but there is another, darker, part of us that does not want to be reminded of our eventual demise.

It’s human nature to become attracted to things that bring us pleasure and avoid things that bring us pain. It is a survival mechanism. It keeps our species alive and allows it to evolve. It helps protect us from putting ourselves in situations where we could come to harm. It becomes detrimental to us, however, when we use grasping and aversion (attraction and avoidance) in an attempt to escape reality itself. Every human being does this, to one extent or another, and doing so inhibits one’s true nature and keeps us from embracing the world completely and seeing objectively the reality of existence.

Rather than seeing reality for what it really is, grasping and aversion allow us to write our own story about the world. This story reflects the fears we have, and is informed by the things in our lives we tend to try to hold on to and the things that we avoid. It’s a veil that informs our view of the world. It is grasping and aversion that creates this veil, and skews our view of the world. By using these tools in an attempt to escape the truth of impermanence, we create what is called Dukkha.

Dukkha is a Pali (Sanskrit) word, often translated into English as “suffering,” yet this is not always the best way to describe Dukkha. It tends to make Buddhism sound like a negative religion. The first Noble Truth is the Truth of Dukkha. If Dukkha is translated as “suffering,” then it pretty much makes it sound like the Buddha is saying “life is suffering.” That’s not very optimistic. It certainly does not make one want to go out, practice Buddhism, and focus on how much everyone is suffering! Unfortunately, there is no real direct translation of the true meaning of Dukkha into English, so it may be best to tell a quick story.

You are a 3-year-old child. It is hot outside, and you have been running around in the park for the bulk of the day. You are thirsty and hungry. Then you remember! Across the street there is a small ice cream shop. It is a shining oasis of cool creamy goodness just a few steps away. A sweet solution to all of your hungry and thirsty woes. You turn to your mother, jump up and down, and repeat “Ice Cream!” over and over again until she relents and takes you over to the shop.

The line is long, seemingly endless, as you wait for your turn to get a scoop. It feels like the server of the ice cream is moving mind-numbingly slow. Finally, after two or three eternities (in Buddhism they call them Kalpas) it’s your turn. You know what you want. You’ve been eyeing the chocolate for a very long time. You point and smile. “One scoop of chocolate!” your mother says. If you were better with words, you’d probably tell her that you are mature enough and voracious enough to handle two scoops now, but you decide not to press your luck and just go with the one scoop. You get your scoop on a waffle cone, because they are the best! The server smiles as he hands you the cone and you wander back outside to sit on a bench and eat the ice cream. Your mouth waters. You can almost taste the icy heaven already as your tongue reaches out toward the scoop….

…. And the scoop of ice cream slips out of the cone and onto the dirty pavement with you even getting the tiniest taste! You stare at the melting mass of broken dreams in disbelief. For a second, your mind just can’t grasp the fact that the ice cream is gone forever. Then reality sets in. The tears well up in your eyes and you tearfully mourn the loss of your tasty treat.

Where is the Dukkha in this situation? The Dukkha is there at any point in the story where the child is focused on something that was not “now.” It is also there at any point where her expectations and reality didn’t mesh. It was present from the very moment the child told stories about the ice cream. When the child was jumping up and down, begging for the ice cream, her mind began to tell her body that the ice cream was going to be wonderful, and was the solution to her current boredom, heat and thirst. It was present as she waited in line, visualizing the time when she would get the ice-cream, and thus attain happiness. Most profoundly, it was present in that final moment of mental confusion when the story she had told herself about the ice cream crumbled before her very eyes, as the ice cream (and therefore happiness) fell from her very grasp. Finally, it manifested in the memory of the ice cream being there, ready to taste, just a moment before- if only she could have that moment back, she would have moved quicker. Or maybe she could have requested a cup instead of a cone and not risked the loss of the ice cream. Either way she spends the last few moments of suffering in the past, wondering about what might have been.

Does this sound familiar? How often do we find ourselves searching for happiness in the future, in what is to come? How many times have we found ourselves longing for the past, remembering some prior happy time and experiencing pain that we can never have that time back? It is a sad fact that many of us spend more time planning for future happiness, and remembering past happiness, than we do actually experiencing the happiness that is there now?

Before this digression into Dukkha, we were going to talk about choices. Three choices to be precise. Two choices lead to more Dukkha. One, chosen repeatedly over our lives, can eventually lead us to liberation. Two are methods of escaping reality. One embraces it. Millions of times in our lives we will be faced with this choice. So, what are the choices we make?

The Path of Materialism:

In Buddhism, this is often referred to the path of sensual indulgence. When we choose this path, we are choosing to attempt to find lasting happiness in the sensual world. The key phrase here is “lasting happiness.” There is a difference between enjoying life and all of the wonderful things our senses can bring to us, and relying upon the physical world to make and keep us happy.

The most extreme travelers upon the Path of Materialism walk this path because they think that reality only consists of things that can be perceived by the senses. Others of us step upon the path because we have temporarily forgotten or choose not to remember that there is more to the universe than that which our senses can detect. Even the most spiritually-minded among us will occasionally find themselves lost on this path.

For those upon this path, there is no “within.” What is there to find in quiet meditation, or contemplation? What could possibly be cultivated inside of us? The physical senses do not operate in the internal world. I cannot see my awareness, nor eat my morality, nor smell my higher self. I have never been able to touch my soul. How can happiness be found there? Since there is no “within,” the seeker turns outward. There she finds the flashing lights, all the bells and whistles, the means of intoxication and physical pleasure.

From this point of view, then, development of self happens outside of us. Our sense of who we are is directly related to the sensual world. The better man is the one with a lot of money or power. The happiest human being is the one with the most attractive partner. It’s a strange occurrence, but when we stop looking within in order to understand ourselves, we begin to value how other people view us. We judge ourselves by other people’s standards. People respect the guy with the highest paying job. So, we get that job. We are judged by the clothes we wear, the house we live in and the car we drive. So, we drive around in the best car we can afford, wear the latest fashions and get the most expensive mortgage we can possibly fit into our budget.

Where we run into an issue is when we realize that our entire sense of self-worth is based upon things that will change. Our clothes will go out of style. We, in fact will physically age – while we may be perceived by society as beautiful and attractive now, that situation will change. As soon as we drive the best car of the lot, we discover that there is a better car. We will meet someone with a nicer house. All of these things change over time. In a desperate attempt of grasping, we do our best to hold on to our current image of ourselves. Billions upon billions are spent each year in an attempt to cosmetically hide the aging process. We continually chase after the better car, the better house, the better way to dress.

In the quiet times, we find ourselves wondering who we really are and what we have become. Constantly we have been measuring ourselves up against society. We do our best to become what society views as a happy person, a successful person, and a good person. Yet, when we look at it objectively we do not know what happy is, nor who we are. So, we do our best to avoid the quiet times.

It is often the case that “happiness” and “stimulus” become interchangeable terms. When we aren’t chasing after the next best thing in the world, we spend our time seeking distraction. Facebook, movies, video games, etc. all become a way that we can distract ourselves and avoid the quiet times. Perhaps we create our own stimulus, taking action to create drama in our lives so that our outer world is constantly moving and holding our attention. Eventually it does not matter whether the drama in our lives is positive or negative, as long as it keeps us focusing on the world around us and not the world within us.

The path of materialism almost always leads to addiction. We could say that materialism itself is an addiction. There are the obvious addictions; addiction to drugs and alcohol, sex addiction, addiction to exercise, etc. There are several other “things” which we could become addicted to, yet we find that all of addiction follows the same basic patterns.

The pattern of addiction is as follows: We find a thing – whether it be a drug, pursuit of materialistic gain, sex, or some other outer stimulus- that gives us happiness and satisfaction. Since everything is temporary, the happiness we felt eventually ends, and we find ourselves looking for it again. After a few times of looking and finding, we discover that, whatever this thing is that gives us happiness or satisfaction, doesn’t make us as satisfied as it once did. So, we seek more of it, or we seek it more often. Eventually, if we are able to break the cycle for just a moment and look at our situation, we discover that we spend more time seeking than we ever do finding. We notice that the times which we are satisfied with life are very much outweighed by the time we spend feeling like we are lacking. We are seeking and feeling unfulfilled more often than we are feeling happy and fulfilled. Those who are ready for a spiritual breakthrough may finally begin to understand that the things they are finding are not the things that they are truly seeking.

This constant cycle of searching, briefly finding, and then loosing happiness and satisfaction places us in a reactionary position. We are no longer in charge of our lives. Instead, our lives are governed by our addictions, our quest for outside validation and our search for stimulus. We find ourselves out of control. Instead of acting in the world, we react to what is happening to us. We float helpless as we become slaves to our desires.

Thus, the Path of Materialist is paved with disappointment, interspersed with moments of happiness that quickly fade. Since we have allowed the outside world to define who we are, we have no true sense of identity. When we don’t know who we are, we certainly cannot fully understand what we want. Instead we follow the torrent of sensation wherever it leads us.

The Path of the Spirit, or of the Intellect:

This second path, is just as much about addiction and self-deception as the path of Materialism. This is also known as the path of asceticism. Seeing the folly of the Materialist path, the Ascetic sees the satisfaction of material desires as a complete waste of time. Rightly, they see that the path of Materialism leads to cycles of self-destruction and does nothing to promote true and lasting happiness. So, what can be done?

Those who tread the Path of the Spirit, or the Intellect, do whatever they can do deny the physical world completely. We use both terms “spirit” and “intellect,” because followers of this path are not always on a spiritual path. Regardless of their belief systems, however, they try to withdraw from the physical world and dwell within the realm of the mind. There are several ways that this may happen.

The Ascetics of old, the ones of whom the Buddha spoke, were those that denied themselves any possible physical pleasure. They ate only enough to maintain life. They were celibate, and wore only rags. While the materialist seeks pleasure in the senses, the Ascetic avoids and even hates the physical world. Since the physical world does not afford lasting happiness, the Ascetic says it should be avoided all together. In the East, we continue to see a lot of examples of Ascetic practitioners; gurus who eat a grain of rice a day and spend all of their time in deep meditation.

In the West, it’s more difficult to find true asceticism. Certainly, there are some religious Orders that have taken vows of poverty or vows of silence and retreat to monasteries to live out their lives. Beyond that, however, we see the path of the Spirit or Intellect manifest in a couple of different ways in the West. Often, we see both of these ways within the same religious tradition. First, we see it manifest in the rejection of the body, and second in the escape into the intellect.

One of the first things we see is a suspicion and dislike for the human body, which includes an unhealthy and damaging focus on the female human body. Here it is important to say that the three paths we are discussing exists in all religious traditions. We’ll see practitioners of any religion treading these paths and our discussion will highlight how the path of the Spirit and Intellect manifest in any religious tradition. This should in no way be read as a judgement or blanket statement about any particular faith. In fact, one of the purposes of this article is to point out that spiritual fulfillment and enlightenment can and does occur in all religious traditions – and all religions, taken the wrong way, lead us away from this goal.

While Western Religion in general has become more liberal over time as society has developed, there are certain fundamentalist sects that continue their suspicion and dislike of the body. We find that, in these religions, we can choose to focus on the nature of sin and its avoidance or on the nature of liberation and redemption.

The body is rejected because it is seen as the root of all sin. Hunger leads to gluttony. The desire for comfort and material gain leads to miserliness and greed. The sex urge leads to lust – in many of these faiths, sex outside of marriage, homosexual sex, and even sex for any purpose other than procreation is considered sinful. Human beings themselves are seen as weak; unable to resist the urges of the body under normal circumstances. Religion then, is seen as a way to incentivize a person to avoid sin.

The nature of Deity is essentially punitive for those fundamentalists who focus on the nature of sin as the driving force for religion. The focus becomes saving oneself from a path of indulging in sin, which can lead to hell and condemnation. We see our particular religious faith as a rescue from the evils of sin, and often our agreement to follow that faith provides us a forgiveness of sin.

This belief that our particular faith (and only our particular faith) contains the keys to salvation and has the authority to forgive sin and rescue an individual from the punishment of hell is one of the main causes of religious conflict and persecution throughout history. We must convert our neighbors so that they are saved. Of course, our neighbors may have a different fundamentalist faith and thus feel the need to convert and save us! Throughout history, this has led to war and persecution. It is likely that we have tortured and killed more human beings in the name of saving them from hell and teaching them the true way to salvation than for any other reason!

The second way in which we can follow the Spiritual or Intellectual Path is by receding into the mind. This also happens in all faiths, and can be an easy companion to the first way we just discussed. In this case, we escape from the physical world, which we still deem as undesirable because no happiness there is permanent. We instead place a mental barrier between us and the world, and immerse ourselves in spiritual study. In many cases, we avoid as much of the world as we can, thinking that if we avoid its pleasures, we’ll also avoid the pain. We know that our physical lives are temporary, so we focus this life on study and preparation for the afterlife. Life is suffering, we are told, so it is only in the afterlife, in heaven or some other idealistic place, that we find eternal happiness.

There is a saying: “It’s easy to be a mystic on a mountain.” When we escape into study, we often only associate with those who think the way we do. This has a tendency to reinforce the attitudes and biases we have cultivated within ourselves. It’s easy then, while doing everything we can to remain withdrawn from the world, to sit in judgement of those acting in the world. In our escapism, we may very rarely place ourselves in a position to make a moral decision, but we certainly feel justified in condemning those around us whom we feel make bad choices. It is very easy to say what someone should have done, or what we would have done, if we were in their positions. It’s much harder to actually live it.

So, while we may be able to escape some of the negative aspects of living in the material world, we do so at our own peril. We may be intellectually stimulated, having read a lot of books and having thought deeply on many of the world’s ills – but we are not challenged because we rarely have the opportunity to apply what we’ve learned to see if our theories really work. In this way, it is possible to spend a lifetime of learning and experience very little growth.

Strangely, a lifetime of avoiding sensual pleasure often leads to an obsession with the same. A person on a strict diet thinks more about the foods they cannot have than a person who eats whatever they want. We can see, particularly in the religions of the West, an unhealthy obsession with sex that comes not from indulgence of it, but rather directly from our denial and demonization of it – it’s a thing we think of as sinful and forbidden, so naturally it occupies our minds a lot of the time. A lifetime on this path leaves us with a body we despise, disdain for any physical pleasure, and full of judgement about other’s actions and lives. We die never having really lived.

A brief look at the Buddha’s life:

The legends and the Sutras say that when Siddhartha was a child and a young man, he had a very rich family. He is even a Prince in some stories. It was predicted of Siddhartha that he would eventually run away and become a monk – that he would either be a great monk or a great king- so his father arranged it that he would always be surrounded by sensual pleasure. His father thought that, if he could keep his son entertained with the good things in this world, Siddhartha would not have time or desire to become a monk.

His family could not hide everything from him however, and it came to pass that on three separate occasions, he was exposed to the suffering of the world. Upon seeing this suffering, Siddhartha vowed that he would find a way to alleviate human suffering (Dukkha). True to his vow, he ran off one night, renounced all of his possessions and spent years studying with the most powerful and renowned Ascetic Monks.

One by one, he studied with the great masters of the time, and became a master himself of various ascetic techniques. Eventually he mastered them all. He had reached spiritual heights. He had denied the physical world to the extent that he was so malnourished that when one looked at him, one could see his internal organs through his skin and his spine behind his belly. Yet he still had not found what he sought. The path to true enlightenment did not come from denying the physical.

Discovering that he was too sick and weak to continue his search for truth, Siddhartha allowed himself to be nursed back to health. He ate a reasonable amount of food each day and began to walk about and exercise. As his health returned, he was once again able to focus his meditations. The other ascetics derided him, saying he was too plump and healthy and had strayed from his true path. Siddhartha ignored them and continued.

Then, beneath the Bodhi Tree, Siddhartha became the Buddha during a meditation. He received the truth of Dukkha and from that, the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. True enlightenment was not to be found only in the material world, nor was it to be found by denying the material world. There was a middle way.

The Middle Way:

The concept of equilibrium is not indigenous only to Buddhism. Its precepts are taught in every religion. The middle way is the path of balance. Regardless of how much or how little the world changes over time, the truth of the middle way will always apply.

True wisdom and lasting happiness comes from embracing the totality of life, and that life is happening right now. The qualities of grasping and aversion discussed at the beginning of this article never happens right now. We practice aversion – escaping into sensual pleasure, or escaping into our brains – because we are afraid of a future pain and we are trying to avoid it. We practice grasping – holding onto a pleasurable experience or holding tightly to our mental world – because we see something good passing away from us and we wish to hold onto it.

Those who walk the middle way understand that life will go in cycles. There will be periods of pleasure and periods of pain, relationships will change, people will pass away – including us. We walk the middle path when we completely accept and do not try to escape from these realities. This acceptance comes with a certain amount of liberation, because we realize how much of our lives was spent worrying about these things; things that we cannot change and that will most certainly happen!

When we let go of our worrying, and our grasping and aversion, then we find that our mind is stilled. We discover that we can truly live in the present. As this unfolds, we discover that our happiness was ours all along, and was not caused by outside forces. Being no longer dependent upon anything outside of ourselves for our happiness, we can simply enjoy them and embrace the conditions of our lives without judgement.

When we are no longer obsessed with ourselves – worrying about losing something we love, about going through periods of hardship, about our own death – we find that we are filled with compassion. We long to alleviate the pain and suffering of others. In fact, the increase of compassion is a sure sign that we are on the right spiritual path; that we are walking the middle way.

I thought of all these things as I walked through the Temple Complex of Wat Pho. The Buddhas were telling me that the spiritual practices of the ancients still ring true today. The world may be moving along at a faster pace and we may have a wider variety of things that can distract us from searching within for our true selves, but the nature of that distraction, the nature of Dukkha, and the liberation from it have not changed. We have cooler toys, but we still face the same basic questions and the same challenges. The Buddhas standing guard at Wat Pho asked us not to forget them, or their practice.

Leave a comment